It Started With Cugnot's Fardier

To begin talking about our forefathers

search for a mode of transport to replace the horse

would necessitate traveling back in time over 300 years.

Inventions (or what perhaps could be better described

as contraptions) utilizing wind power and even elaborate

clockwork gearing were all tried, up to the advent of

steam power.

The oldest surviving self-propelled vehicle,

Cugnot's 1770 “Fardier” owes its preservation

to the fact that on its trial runs it ran amok and knocked

down a wall! Put into store, it survived the French

Revolution, was acquired by the Conservatoire des Arts

et Métiers in Paris in 1799, and has been a major

exhibit there ever since.

It was followed by a number of even less practical

designs from optimistic French, English and American

engineers, and it was not until 1801 that the first

successful road carriage appeared. The brainchild of

Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick, the road

carriage would in-turn lead to the development of his

London Carriage of 1803, which made a number of successful

runs before being dismantled to power a hoop rolling

mill.

Trevithick lost faith in the practicability of

his own inventions, and although they came very close

none were perfected. Other inventors of the day could

see his vision, and so began developing a range of supposed

“vehicles”, although they were all ill-founded

and better suited to science fiction.

The ideas ranged from machines driven by articulated

legs, tiny railway engines running inside a drum like

squirrels, the use of compressed air and, alarmingly,

gunpowder!

The Advent Of The Steam Engine

Then, between 1820 and 1840, came a golden

age of steam, with skilled engineers devising and operating

steam carriages of advanced and ingenious design; men

like Gurney, Hancock and Macerone all produced designs

which were practicable, capable of achieving quite lengthy

journeys and operating with a relatively high degree

of reliability.

Walter Hancock, a better mechanic than businessman,

operated his steam coaches on regular scheduled services

in London in the 1830s, but his finances were quickly

depleted by unscrupulous associates. Hancock eventually

called it a day after 12 years of experimentation had

brought him little more than unpaid debts with the associated

hostility of his creditors.

And as you would expect, the politicians of the day

displayed a total lack of vision. Many were convinced

that the “Steam Carriage” would prove a

threat to the thousands whose livelihood depended on

the horse, and so they implemented tolls on the turnpike

roads.

An 1831 Parliamentary Commission, though largely

favorable to the steam carriage, failed to prevent the

introduction of the road tolls – thus delivering

a near fatal blow to the builders of steam carriages.

It would be a few years later, with the advent of the

railway age, that would finally put to rest the “Steam

Carriage” industry.

Railway engines had the advantage of running on smooth,

level rails, while the Steam Carriages were forced to

use uneven, badly maintained roads. The Railway was

big business, providing huge profits and returns for

the railway owners. As you can imagine, big business

had the ear of the local politicians of the day.

They

were quick to point out that the Railways major competitor,

the Steam Carriage, could be considered unsafe given

they were using “public” roads filled with

half-witted pedestrians, and so in 1863 legislation

was passed requiring every Steam Carriage to have a

man with a red flag must walk ahead. It was only the

development of the bicycle in the 1860s which would

allow the hapless public to again tour by road.

The Internal Combustion Engine

While the

internal combustion engine appeared early

on in the history of the motor vehicle, it would take

over three-quarters of a century for it to be perfected

to the level where it could be used in a vehicle capable

of running on the roads. The 1805 powered cart of the

Swiss Isaac de Rivaz was little more than an elaborate

toy, capable of crawling from one side of a room to

another, while the 1863 car built in Paris by JJ. Etienne

Lenoir took three hours to cover six miles. It was not

until the mid-1880s that the first successful petrol

cars appeared, developed independently by two German

engineers, Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz.

It was Karl Benz’s vehicle that was incontestably

superior. While Daimler had “adapted” a

horse drawn vehicle, Benz had designed a vehicle from

the ground up, utilizing new technologies from the cycle

industry for his inspiration. The three-wheeled vehicle

that Benz developed would go into limited production

– it being described in his catalogue as “an

agreeable vehicle, as well as a mountain-climbing apparatus”.

By 1888 Daimler had decided to concentrate on selling

his engines as a universal power source, but interestingly

neither would find immediate success.

The Steam Engine's Last Gasp

Instead the Steam Carriage made a final comeback, particularly

with some of the advanced designs of the Boll family

of Le Mans. These carriages, built between 1873 and

the mid-1880’s, were to pioneer such advancements

as independent front suspension. Meanwhile one Léon

Serpollet , a blacksmith's son, conceived a 'flash boiler'

capable of the instantaneous generation of steam.

Serpollet

would soon be the proud bearer of the very first driving

licence to be issued in Paris. And while the Comte De

Dion and his engineers Bouton and Trépardoux

built some excellent steam vehicles during the 1880’s

and early 1890’s, they were to achieve their greatest

fame as manufacturers of light petrol vehicles, from

1895 onward.

Cugnot's 1770 “Fardier”

survives to this day because it crashed on its

trial run...

The Bollée Mancelle Steam

Carriage of 1873 would require a man to lead

it waving a red flag should it contemplate using

London roads...

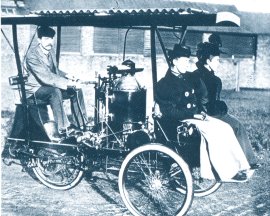

This 1895 Tri-Car used a Leyland

steam lawnmower engine, and its mid-mounted

location had absolutely nothing to do with improving

handling...

In the early 1900's the most

famous of the "Gas Buggies” was the

Curved-Dash Oldsmobile...

Arguably Ford's greatest achievement

was to introduce the 1908 Model T, a car that

would became so popular that he was forced to

introduce the car industry's first moving production

line... Arguably Ford's greatest achievement

was to introduce the 1908 Model T, a car that

would became so popular that he was forced to

introduce the car industry's first moving production

line...

The Twin Cylinder Renault AX

helped ferry troops to the battle of Marne and

save Paris in 1914 at the hight of World War

1...

Hispano-Suiza put their aero

engine expertise to full account in the 1919

32CV of 6.6 litres, a splendid automobile featuring

servo-assisted four-wheel brakes and delightful handling characteristics...

After the war it would take until

1922 for the motor industry to get back on course

with a second generation of post-war popular

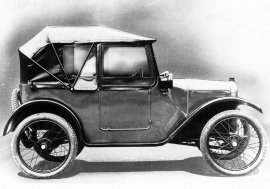

cars - most notable was the Austin Seven... After the war it would take until

1922 for the motor industry to get back on course

with a second generation of post-war popular

cars - most notable was the Austin Seven...

During the 1920's features were

introduced to make motoring more comfortable

and safer. Windscreen wipers, electric starters,

low-pressure tyres and, first standardized on

the 1928 Model A Ford, safety glass... During the 1920's features were

introduced to make motoring more comfortable

and safer. Windscreen wipers, electric starters,

low-pressure tyres and, first standardized on

the 1928 Model A Ford, safety glass...

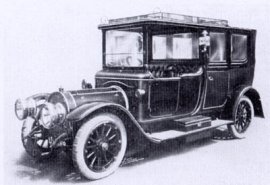

The Delaunay-Belleville may have

been the very best of French cars and and favourite

marque of the Tsar of Russia, but that wasn't

enough to save it during the 1920's... The Delaunay-Belleville may have

been the very best of French cars and and favourite

marque of the Tsar of Russia, but that wasn't

enough to save it during the 1920's...

During the 1930-35 period streamlining

became the vogue, as evidenced in such classics

as the Chrysler Airflow...

Though most cars still retained

running boards, lower door edges gave a lower,

more bulbous look, accentuated by the adoption

of wings with side panels, often blended into

the radiator and bonnet, as seen here on with

the Singer Airstream...

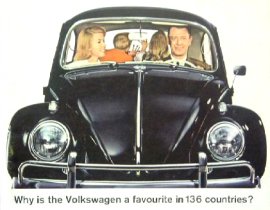

Volkswagen went from strength

to strength after WWII, despite opinions from

British experts - and from Henry Ford II - that

the VW was too noisy and uncomfortable to be

competitive... Volkswagen went from strength

to strength after WWII, despite opinions from

British experts - and from Henry Ford II - that

the VW was too noisy and uncomfortable to be

competitive...

Companies like Crosley stood

little chance against the "Big Three"

during the 1950's... |

The 1889 Paris World Exhibition

The biggest turning point for the automobile, and the

internal combustion engine, was arguably the 1889 Paris

World Exhibition. It was at this exhibition that French

engineers Panhard and Levassor saw the Daimler 'Steelwheeler'

car powered by the Daimler vee-twin engine. Levassor's

lady friend, an astute widow named Louise Sarazin, held

the French rights to the Daimler engine in succession

to her late husband, and Panhard and Levassor began

manufacturing these power units in 1890.

They could,

however, see no future for the motor car, and so granted

the right to use Daimler engines in self-propelled vehicles

to Peugeot (then an ironmongery and cycle firm) who,

as luck would have it, had just made the decision not

to proceed with the production of the “Serpollet

Steamers”.

Around the same time, and also in France, Emile Roger

managed to sell a handful of Benz cars. Ironically Roger

would garage his first Benz in Panhard and Levassor's

workshop. But things were about to change, particularly

with Benz’s first four-wheeler, the 1893 Viktoria.

Peugeot were already established as motor manufacturers

by that date, for in 1891 they had actually sold 5 cars,

boosting production to a dizzy 29 the following year.

The success of the Peugeot cars forced Panhard and Levassor

to reconsider their early opinion of the horseless carriage,

and, after building a couple of crude dogcarts with

the engine at the rear, Levassor devised the famous

Systéme Panhard, with the engine at the front

driving the rear wheels via a sliding pinion gearbox

inspired by the mechanism of a lathe, a layout which

endures on to this day.

Development in America

In America, the motor car was evolving quite independently

of the goings on in Europe. During the first part of

1891 a petrol powered friction-driven three-wheeler

built by John W. Lambert of Ohio City made its first

tentative runs. In 1895, America's first motor manufacturing

company was founded by the Duryea brothers, Charles

and Frank (whose

prototype dated from 1893); the following

year they exported a couple of vehicles to Britain.

Perhaps the railroads of the day considered the emerging

automobile technologies as impinging upon their turf,

or a general population lacking in vision, for whatever

the reason there was little interest in the new motor

vehicles (be they home-grown or imported), although

the so-called “father of the British motor industry”,

H. J. Lawson, succeeded in parting a good many credulous

investors from large sums of money.

Lawson knew that, for the automobile to become successful,

the ridiculous legislation requiring a red flag waver

to walk in front of any vehicle would have to be repealed.

Fortunately for Lawson he had friends in high places,

and on November 14 1896 he organized a commemorative

run to Brighton to celebrate the raising of the speed

limit to 12 mph.

Ironically many of the participating

automobiles would travel much of the distance by train,

while the first car home, a Duryea, was not one of the

marques under Lawson's control, he having purchased

at great expense most of the motor car patents in an

ill-founded attempt to monopolize the British car industry.

Demand for motor cars continue to grow steadily during

the latter part of the 1890s, and by now the Benz had

become the world's most popular car, with the 2000th

production vehicle being delivered in 1899. Motoring

was still the sport of a few rich eccentrics, however,

and many people, particularly those in country areas,

were yet to even see a car!

The 1000 Miles Trial

In an effort to “showcase” the new technology

to the masses, the Automobile Club of Great Britain

and Ireland held its famous 1000 Miles Trial, taking

in most of the major cities of England and Scotland.

A total of 65 cars, many English Daimler and MMC models

built by Lawson's empire, set out from Hyde Park Corner,

London, in April; the majority finishing the run without

major mishap, proving that the car had at last become

a reliable mode of transportation and offered a clear

alternative to horse and buggy.

The Turn of the Century was ushered in by 'the car

of the day after tomorrow', the Mercedes, designed by

Daimler's engineer, Wilhelm Maybach. The contract to

produce the first batch of 30 cars had been signed within

a month of Gottlieb Daimler's death in March 1900.

They

had been ordered by the wealthy Austro-Hungarian Consul

at Nice, Emil Jellinek, who insisted that they be christened

after his daughter Mercedes, a name which found such

favour with the wealthy car-buying public that all German

Daimler cars were soon known by that name.

The advanced design of the Mercedes, which combined

in one harmonious whole elements such as the honeycomb

radiator, pressed steel chassis and gear-lever moving

in a gate rather than a quadrant, 'set the fashion to

the world' and soon many high-priced cars were copying

its layout; even comparatively small cars like the Peugeot

were built on Mercedes lines.

These cars did not, however, represent the popular

motoring of the early 1900s; this was the province of

single-cylinder runabouts like the De Dion and the Renault.

In the US the designers favoured the light, but considerably

more temperamental, steam cars such as the Locomobile;

these were soon followed by “Gas Buggies”,

of which the most famous was the Curved-Dash Oldsmobile.

Ford vs The Association of Licenced Automobile Manufacturers

That the US automobile industry was taking some time

to advance can be found in the monopolistic attitude

of the time. A patent lawyer named George Baldwin Selden

had drawn up a 'master patent' for the motor vehicle

in 1879, published it in 1895 and claimed that all gasoline-driven

vehicles were infringements of that patent. His claims

were eventually given commercial teeth by the Association

of Licenced Automobile Manufacturers, established to

administer the Selden Patent in 1902, to which most

major American car firms were persuaded to belong.

It was Henry Ford, who had founded his Ford Motor Company

in June 1903, that decided to take the fight up to Selden

and the ALAM. Proceedings were initiated in 1904 and,

after lengthy litigation, the ALAM built a car to Selden's

1879 design while Ford built a car with an engine based

on that of the 1863 Lenoir. Ford won the day in 1911

- not long before the Selden Patent would have expired

anyway - but the victory established him as a folk hero.

The Model T

Ford's great achievement, after five years' work, was

to introduce in October 1908 the immortal Model T, which

became so popular that he was forced to introduce the

car industry's first moving production line in order

to build enough cars to satisfy demand. His 'Universal

Car' changed the face of. motoring; over 16.5 million

were built before production ended in 1927, truly 'putting

the world on wheels.

Though the Edwardian era saw motoring become more popular,

on the other hand it also saw the finest and most elegant

cars of all time, built to a standard of craftsmanship

which could never be repeated. After World War One,

many of the great marques faded away in a genteel decline:

Delaunay-Belleville, 'the Car Magnificent', the favourite

marque of the Tsar of Russia and one of the very best

of the French cars of the pre-1914 era, became just

a petit bourgeois in the 1920s.

Napier, the British company which popularized the six-cylinder

engine, enjoyed perhaps even greater acclaim than its

rival, Rolls-Royce, while its sales were controlled

by the overly pompous Selwyn Francis Edge; when Napier

gave him a £160,000 “Golden Handshake”

after a dispute over policy in 1912, however, the company's

fortunes seemed to leave with him. Edge, having agreed

to leave the motor industry for seven years, became

a successful Sussex pig farmer; Napier built very few

cars after the war, concentrating instead on its aero

engines.

The Growth In Popularity Of The Cycle Car

The European car industry was under considerable economic

pressure from that in the US. The latter was manufacturing

automobiles using predominantly unskilled labour on

their new production lines, while the former relied

heavily on a pool of highly skilled, lowly paid craftsmen,

all of whom were expected to take pride in their work

and consider the automobile a piece of craftsmanship

rather than an object of mass production.

Inevitably

it was the big luxury cars that stood little chance

– for they represented only a tiny fraction of

the potential market for the motor vehicle and, even

if their production had not been decimated by the drying

up of the car market as a result of the war, they would

inevitably have died out as a result of the social changes

in the post-war world.

Europe, indeed, experienced an outburst popular motoring

in the 1910-14 period which owed nothing to American

concepts of mass production; instead, it grew out of

the motorcycle industry, whose engines, single-cylinder

or Vee-Twin, offered lightness and power

Optimistic

enthusiasts installed these engines in chassis of often

suicidal crudeness, with cart-type centre-pivot

steering in many cases, as well as other un-mechanical devices

such as wire cables coiled round the

steering column

instead of a conventional

steering box and drag link,

belt and pulley transmission and tandem-seat layouts

with the driver in the second row.

These crude devices,

known as cycle-cars, flourished predominantly in England

and France; attempts to mimic their success in America

failed because they were simply unsuited to the very

different motoring environment.

While the cycle-cars were short-lived, it was during

this period that the future direction of the automobile

industry could be seen, in new “light” cars

such as the Morris Oxford, the Standard and the Hillman.

These cars were all built on the one principle, to afford

large vehicle characteristics on a smaller scale, using

cheap, economical and easy to manufacture engines with

capacities around the 1000cc mark. These admirable machines

were to be the pattern for the popular family cars of

the 1920s.

The Combustion Engine's Role In World War 1

During the first war it was the

internal combustion

engine that afforded new mobility to the infantry who,

before hostilities in Europe came to a standstill in

the trenches, could be rushed to reinforce weak points

in the front line - most notably when the French General

Gallieni sent 6000 reinforcements to repel Von Kluck's

attack on Paris in 1914.

Motorcycles were used to issue

military dispatches, while armoured cars and tanks would

become an increasingly familiar sight on the front lines.

But perhaps the biggest advance of the

internal combustion

engine was in the air, aerial combat adding a new and

deadly dimension to modern day warfare.

Post War Boom, and Bust

In the post war period there was an automotive boom

time, especially in Britain and France. The established

manufacturers had little hope of meeting the new demand,

and so a new cottage industry of companies manufacturing

light cars and cycle-cars from proprietary components

soon developed. Most however were to only find commercial

failure.

If the European car industry had any chance against

the US giants, the notion of mass-production needed

to be embraced. André Citroén, a former

gear manufacturer, decided to bring Ford-style mass-production

to France. We would enjoy an immediate success with

his 10bhp launched in 1919. However, the rise of Citroén

spelt doom for the dozens of hand-assemblers who clustered

most thickly in the north-western suburbs of Paris.

The boom collapsed in 1920-21, speeded on its way by

strikes, hold-ups, shortages, loss of stock market confidence

in the car industry, restrictions on hire-purchase sales,

costlier raw materials, and the introduction of a “horsepower”

tax in Britain. Only the fittest survived: Ford, whose example was

followed by a number of American and European makers,

cut prices in order to boost falling sales.

In Ford’s

case, he was able to compensate for the loss on the

cars by compelling every dealer to take $40 worth of

spare parts per car – the spare parts affording

no price reduction. Even the mighty Ford was, however,

forced to close down for some months to clear unsold

stocks. It was not until 1922 that the motor industry

was back on course and a second generation of post-war

popular cars began to emerge, most notably the Austin

Seven.

Many of the cars of the 1920’s profited from

the technology of the aero engines developed during

the war, cars such as the overhead camshaft Hispano-Suiza

V8. Wolseley built this engine under licence and used

an overhead camshaft on their post-war cars, but it

was not until after the 1927 takeover by Morris that

this Wolseley design realized its full potential, especially

in MG sports cars.

The Automobile Matures

Hispano-Suiza put their aero engine expertise to full

account in the 1919 32CV of 6.6 litres, a splendid automobile

featuring servo-assisted four-wheel

brakes and delightful

handling characteristics, whose overall conception was

several years ahead of any of its rivals. Meanwhile

Bentley, who had built rotary aero engines during the

war, brought out an in-line four with an overhead camshaft

in 1919 (though it was not put into production until

1921); this 3-litre was to form the basis of one of

the worlds most immortal sporting cars.

Many leading manufacturers adopted the overhead camshaft

layout during this period, but Rolls-Royce, whose aero

engines had used this layout, stuck resolutely to side

valves on their cars until the advent of the 20 in 1922;

this had a pushrod OHV configuration, although the Silver

Ghost would retain side

valves till the end.

Oddly enough, apart from honourable exceptions like

the Hispano, it was the cheaper cars which pioneered

the use of

brakes on all four wheels, one of the most

positive advances in car equipment in the early 1920s.

Possibly it was felt that luxury cars would be handled

by professional drivers, who would be less likely to

indulge in the kind of reckless driving that would require

powerful brakes! Moreover, some American popular car

makers, appalled at the cost of retooling their cars

to accept

brakes on the front wheels, actually campaigned

against their introduction on the grounds that they

were dangerous. Ralph Nader would have had a field day!

As the decade wore on, more features designed to make

motoring more comfortable and safer became commonplace-windscreen

wipers, electric starters, safety glass (first standardized

on the 1928 Model A Ford), all-steel coachwork, saloon

bodies, low-pressure tyres, cellulose paint and chromium

plating all became available on popular cars. Styling

and the annual model changes became an accepted part

of the selling of motor cars, bringing with them huge

tooling costs which could only be borne by the biggest

companies. Many old-established firms were simply unable

to keep up, being swept away by the onslaught of the

depression in 1929.

The Depression

Was it the depression that made people less inclined

to enjoy the concept of open-air motoring, or was it

the practicalities of fending off the elements. Whatever

the case, the switch from open-tourer to saloon bodies

was well under-way by 1931; by this time some 90% of

all cars being “Tin Tops”, a complete reversal

on the number produced only 2 years earlier.

In a concession to the difficult economic times, manufacturers

were also forced to develop smaller engines, and in

turn lighter car bodies and lower ratio gear boxes.

As a result, the cars of the day were required to rev

hard to afford any pretence of performance, and naturally

their bores wore alarmingly. The days when durability

was a feature taken for granted on all but the shoddiest

of cars seemed long past.

The design of cars now began to change radically as

well. The demand for more capacious

bodywork on small

chassis led to the engine being pushed forward over

the front axle. The

radiator became a functional unit

concealed behind a decorative grille which became more

elaborate and exaggerated as the decade wore on.

During the 1930-35 period

streamlining became the vogue,

as evidenced in such classics as the Chrysler Airflow,

the Singer Airstream and the Fitzmaurice-bodied Ford

V8. Even on more staid cars, the angularity of line

that had characterized the models of the late 1920s

gave way to more flowing contours. Though most cars

still retained running boards, the separate side valances

were eliminated by bringing the lower door edges down

to give a lower, more bulbous look, accentuated by the

adoption of wings with side panels, often blended into

the

radiator and bonnet.

The swept tails of the new-style coachwork now concealed

a usually well laid out luggage compartment, a feature

sadly lacking on most 1920s models, which usually boasted

a luggage grid and nothing more. By contrast with the

cars of the 1920’s, those of the 1930’s

offered considerably greater comfort and convenience.

One problem, however, was that the stylist had taken

over from the engineer and designer; thus little thought

was given to their

aerodynamics or road holding ability.

While there was no going back to the old-fashioned designs,

many wished they could!

New suspension systems, especially independent front

springing, also brought their own

handling problems.

In fact, some cars had to be fitted with bumpers incorporating

a harmonic damping device to prevent them from simply

shimmying right off the road on their super-soft springing.

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom, with some manufacturers

producing some excellent cars. Morris and Austin would

continue to build soundly engineered small cars (though

Herbert Austin was distinctly upset when his designers

insisted on moving the

radiator behind a dummy grille.

Henry Ford was personally involved in the development

of two new models, the 8hp Model 19Y and the V. Both

cars were released in 1932, and were instantly and deservedly

successful.

In France the famous

front wheel drive Citroén

would make its debut in 1934. Unfortunately the development

costs had all but bankrupted André Citroén,

and he was forced to sell out to Michelin. Of the cars

with more sporting pretentions, the SS marque were producing

beautiful looking, beautiful

handling and beautifully

built cars, and for a very reasonable price.

The same year that the SS Jaguar was launched (1936)

Dr Ferdinand Porsche built the

prototype Volkswagens,

the 'Strength through Joy' cars sponsored by the Nazi

Party and intended to be sold to the German public.

Was the argument to bring cars to the German masses,

or was it to prevent them purchasing foreign manufactured

cars? Whatever the reason, this most popular of designs

would go on to sell over 20 million and establish itself

as the most popular car of all time (and we will not

be drawn into comparisons with the Toyota Corolla).

Few Volkswagens, however, were built before the war

(though the design was readily adapted for military

purposes).

In many ways the 1930s were a watershed - they saw

the last of the big luxury cars from makers such as

Hispano-Suiza, Duesenberg and Minerva, as well as the

end of many small, independent manufacturers and coachbuilders

(victims of the swing to mass-produced cars with pressed-steel

bodies). The motor industry had reached the point where

it had become vital to the economic well-being of the

major industrialized countries. Now it was to prove

just as vital in providing weapons of war.

Europe Braces For War...Again

In Britain, five of the largest motor manufacturers

set up “shadow factories” in the late 1930s

- used in the production of aero-engine and parts in

the event of war. This foresight would see them manufacturing

many thousands of aero engines and complete aircraft

during the hostilities. Ford joined the fold soon after

the outbreak of war, building Rolls-Royce Merlin engines

on a moving production line in Manchester, while in

the USA Ford mass production expertise was given its

greatest test in manufacturing Liberator bombers on

a gigantic production line at Willow Run, Michigan.

From the ubiquitous Jeep, through staff cars, trucks,

tanks and powerboats to the biggest bomber aircraft,

the motor industry played a crucial role in World War

Two. Re-adapting to peacetime production was, however

' to prove almost as big a test of the industry's abilities.

After the war there was a huge materials shortage –

but despite significant government interference most

car manufacturers were soon to return to production.

The first examples to roll off the production lines

were inevitably only slightly modernized pre-war models,

although some manufacturers such as Armstrong-Siddeley

were able to immediately manufacture all-new models.

Despite shortages of fuel and tyres, there was a vast

demand in Europe for cars. Despite a huge shortage in

Britain, the government mandated that manufacturers

export half their output – you could be forgiven

for thinking the best way to win a war is to loose it

first, Speculators (scalpers) soon entered the fray,

buying new cars and selling them at an inflated profit

– soon purchasers were forced to sign a 'covenant'

guaranteeing that they would not resell for initially

one year, this later being extended to two years.

There was much talk of technical developments arising

from wartime projects, but devices such as automatic

transmission were only generally adopted in America,

and reports that hydraulic suspension, or springing

by rubber or torsion bars, were about to be adopted

on British cars proved to be more than a little premature.

Indeed, some makers seemed unready to come to terms

with the future, as one report noted: 'Since wind resistance

is an important factor in brake performance,

streamlining may lead to braking difficulties, as was shown in experiments

carried out in France'.

European manufacturers faced the daunting task of having

to rebuilding their often totally destroyed manufacturing

plants. The French automotive industry had sustained

the biggest loss of machine tools and equipment, most

being shipped to Germany under the occupation. The German

industries had sustained considerable bomb damage, and

having the country divided into two entities posed even

bigger problems.

The Reichsmark was replaced by the Deutschmark, creating

an effective devaluation of around 100%. Nevertheless,

the country's most prolific manufacturer, Volkswagen,

continued to make progress despite opinions from British

experts - and from Henry Ford II - that the VW was too

noisy and uncomfortable to be competitive. And though

the BMW factory had ended up in the Russian Zone, the

first-and only- 'War Reparation' design to come out

of Germany became the BMW-based Bristol 400.

A shortage of sheet steel and

tyres also helped to

keep production to about a sixth of the 1938 level in

1946-48, though some recovery was apparent by 1949 when

the first post-war car show was held in Paris –

by this time production had risen to about four times

the 1938 monthly level.

The 1950's, A Period Of Turmoil

By the time of the 1950’s the motor industry

was entering a period of traumatic change. Those brave

attempts by independent companies like Kaiser and Crosley

to carve a foothold in the American market against the

corporate giants of the Big Three (Ford, GM and Chrysler)

were to quickly amount to nothing. Old and well established

independents like Packard, Nash and Studebaker were

in decline and would soon vanish, either by attrition

or by merger. The American car industry had become stereotyped,

offering up to the public a diet of overly large, poor

road holding behemoths being driven by large 6 cylinder

or even larger V8 engines.

The 50’s ushered in the era of the exaggerated

tailfin and the grinning chrome grille, and the 'performance

car' capable of superlative top speeds, but being unsafe

around any corner. Small “compact” cars

were developed in 1959, of particular importance to

Australians was the Ford Falcon and Chrysler Valiant

– both becoming a staple of the Australian family

alongside the GM Holden. Then there was the unorthodox

rear-engined Chevrolet Corvair, bringing Ralph Nader

notoriety with his best selling book “Unsafe at

any Speed”.

Mergers and amalgamations were not only confined to

the US. In Britain, Austin and Morris would join, but

this was never a happy association. Commentators predicted

a decline in the British automotive industry –

and they were uncharacteristically correct. BMC (British

Motor Corporation), British Leyland and others, all

producing small family cars, were unable to crystal

ball their own demise at the hands of union trouble

and the emergence of the Japanese as an automotive power

house.

The Importance Of Fuel Efficient Cars

Fuel economy became even more significant after the

1956 Suez War, when petrol was rationed in many countries,

and the event created a new breed of cycle-cars, which

today we refer to as “Bubble Cars”, such

as the Heinkel, Messerschmitt and Goggomobil. The “Bubble Cars” may have been “cute”,

but they were primitive devices and not well liked at

the time.

Their saving grace was their fuel economy

– should someone design a comfortable AND economical

car they would be doomed. That person was Alec Issigonis

– and his design - the 1959 Mini Minor. Now “Cheap

and Cheerful” could also mean decent engineering,

comfort and handling. The Mini’s layout of front-wheel

drive and transverse engine was to set the pattern for

the coming 20 years and more.

But the 1950s had their glamour cars, too: Britain

produced the big Healeys, the Triumph TRs and the first

MG to abandon the per perpendicular lines of the 1930s,

the slippery profiled MGA, even available with a temperamental

twin-cam engine; Italy built big, powerful sports cars

like the Ferrari America and Super America; France,

which had taxed the Grand' Routiers like Delahaye out

of existence, introduced the avant-garde Citroen DS;

and Germany, free of any war repatriation responsibility,

were to release the distinctive

Mercedes 300SL Coupe – one of the most highly sought after sports cars

to this day.

Also see:

The History of Australian Motoring - Looking Back On Forty Years of Motoring by W. H. Lober

The Sports Car

Great British Pre-War Sports Car

Founding Fathers Of The Automotive Industry

The Automotive Industry, Pre World War 1

The Automotive Industry, Between The Wars

The Automotive Industry,

Post War

The Weird And Wonderful Car Inventions